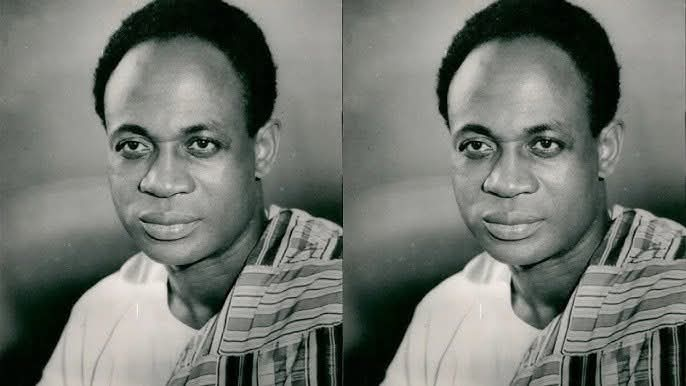

According to Manaseh Azuri Awuni, an investigative journalist said Overthrowing Dr. Kwame Nkrumah is hardly an achievement worthy of naming Ghana’s international airport after Lt. General Emmanuel Kwasi Kotoka.

Nkrumah, like all leaders, had flaws. His greatest shortcoming was his drift from democracy toward the end of his tenure. He became increasingly paranoid — something his defenders attribute to the multiple assassination attempts on his life and Western interference aimed at his removal. While these factors might explain his actions, they do not entirely absolve him of his high-handedness.

That notwithstanding, Nkrumah was not the worst thing that ever happened to Ghana. Those who toppled him, often with backing from narrow Western interests, should not be celebrated with national monuments.

Those who suffered under his rule deserve a voice, yes — but so too do the millions who gained access to education, healthcare, and opportunity because of his vision and sacrifice. The Nkrumah debate should not be framed solely around his virtues or failings; it must consider the totality of his impact.

Being a president, whether elected democratically or through a coup, should not in itself merit the honour of having national landmarks named after you. In that regard, someone like Dr. J.B. Danquah is far more deserving of such recognition than Kotoka. (And for the record, one shouldn’t merely buy into the unverified narrative that Danquah was a CIA agent — his contributions to Ghana’s intellectual and constitutional development speak for themselves.)

Consider Martin Luther King Jr. — he was never a head of state, yet he has more monuments in his honour than most American presidents and even a national holiday. True honour should stem from service, not from holding power.

It is therefore untenable for Paul Adom-Otchere to insist that Ghana owes its current peace and stability to Kotoka. The 1966 coup did not usher in stability; the years that followed were marred by further coups and political turmoil. To credit Kotoka for Ghana’s peace today is a distortion of history.

Paul argues that Nkrumah’s overthrow deterred future leaders from overstaying their welcome in power. But if that logic holds, how do we explain countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, where Patrice Lumumba — overthrown and assassinated even earlier than Nkrumah — was replaced by decades of chaos and instability?

And where, then, does that leave Jerry John Rawlings? Like Kotoka, Rawlings seized power unconstitutionally. Yet, after a decade of rule, he transitioned Ghana into the Fourth Republic and handed over power peacefully in 2001 — a precedent that strengthened our democracy. Ghana has endured severe economic and political storms since then, but our democracy has held firm.

To bypass Rawlings and others who fought to stabilise Ghana’s democratic institutions, and to instead attribute the nation’s peace to Kotoka, is intellectually difficult to justify.

And by the way, comparing Kotoka’s coup to the liberation struggles of Oliver Tambo and Nelson Mandela is misleading. The Western powers that backed Kotoka’s coup were the same forces that branded Mandela and Tambo as terrorists for resisting apartheid. Their struggles cannot be equated.